It was more than 35 years ago that Bruce Feirstein’s (1982) New York Times bestseller started the conversation: Real Men Don’t Eat Quiche. Satirical as the nature of the book may have been, it’s true that quiche-eating was considered the antithesis of everything a red-meat man believed in. Beef and lamb were fine, but pigs were problematic. Bacon was fine—nice and greasy, able to cure a hangover, great with ketchup or brown sauce; an honorary sausage. Roast pork with crackling—despite its colour—was just about up there with the others. Ham and gammon, however, were a bit suspect. Chicken, too, was nearly a vegetable. For those who grew up more exposed to the media of the 21st century, the spirit may easily be summed up in the view of Nick Offerman’s Parks and Recreation character Ron Swanson: “Fish, for sport only, not for meat. Fish meat is practically a vegetable”.

This stereotyping of quiche-eating men went beyond dietary preferences. It was also a presumed signifier of males who might drink wine rather than beer, who might make the quiche themselves, and do the washing up afterwards; men who would advocate women’s rights, gay rights, and share domestic tasks like shopping, cleaning, laundry and childcare with their partners. It implied an association with the vanguard of political causes and with being sensitive, radical, nonconformists who wore the appropriate lapel badges.

Although the book sold over 1.6 million copies, it’s likely that many of its readers considered it to be nothing more than an elaborate joke at the expense of feminism and woolly liberal thinking. Even taking the original claims at face value, it’s easy to dismiss them as belonging to an earlier age—a time when pizza and kebabs were exotic late-night or early-morning takeaway alternatives after the fish & chip shop had closed, and when the rice and pasta packets in at least one major British supermarket were to be found in the aisle labelled “Foreign Food”.

“American men are all mixed up today…There was a time when this was a nation of Ernest Hemingways, real men. The kind of men who could defoliate an entire forest to make a breakfast fire — and then wipe out an endangered species while hunting for lunch. But not anymore. We've become a nation of wimps … And where's it gotten us? I'll tell you where. The Japanese make better cars. The Israelis better soldiers. And the rest of the world is using our embassies for target practice,” Feirnstein wrote.

But eating has a higher profile than it did four decades ago. It’s not just the taste of the plated product that’s considered today, but also the methods of preparation, the provenance and purity of the ingredients, the miles required to source the produce, and the ethical status of production processes. Food groups no longer correspond with social groups and there’s a greater awareness of the virtues of healthy eating. Whether you prefer vegan or vegetarian, kosher or halal, molecular gastronomy or street food, ethnic or fusion, or any other of the multiple alternatives, you wouldn’t expect your gender to be determining your choice, nor be defined by it, would you?

Men experience conflict between their personal preferences and what they think might be expected of them. When they have time to evaluate their decisions, men tend to override their personal preferences and conform to presumed gender expectations. In contrast, women seem to be less concerned with making gender-congruent choices.

Research published in Social Psychological and Personality Science by David Gal and James Wilkie from the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University in Illinois revealed there are still strong correlations between food choices and gender. Gal and Wilkie noted that several earlier studies had established that “masculine” dietary preferences included alcohol, meat, and generous portion sizes whereas vegetables, fruit, fish, and sour dairy products such as yogurt were associated with femininity. Additionally, products with rounded edges (whether foodstuffs or material objects) tended to be seen as relatively feminine, whereas products with sharp edges tended to be seen as relatively masculine. Pursuing ideas developed from these studies, Gal and Wilkie found that when choosing from an “either/or” menu, men were much more likely to select the dishes with the more “masculine” appeal (in terms of foodstuff, description and shape) if they had time to make a “considered” decision, significantly more so than if they had to make a snap decision (within ten seconds). In contrast, the likelihood of a woman to choose the “feminine” selection from the same either/or alternative remained constant regardless of the time available in which to make their choice.

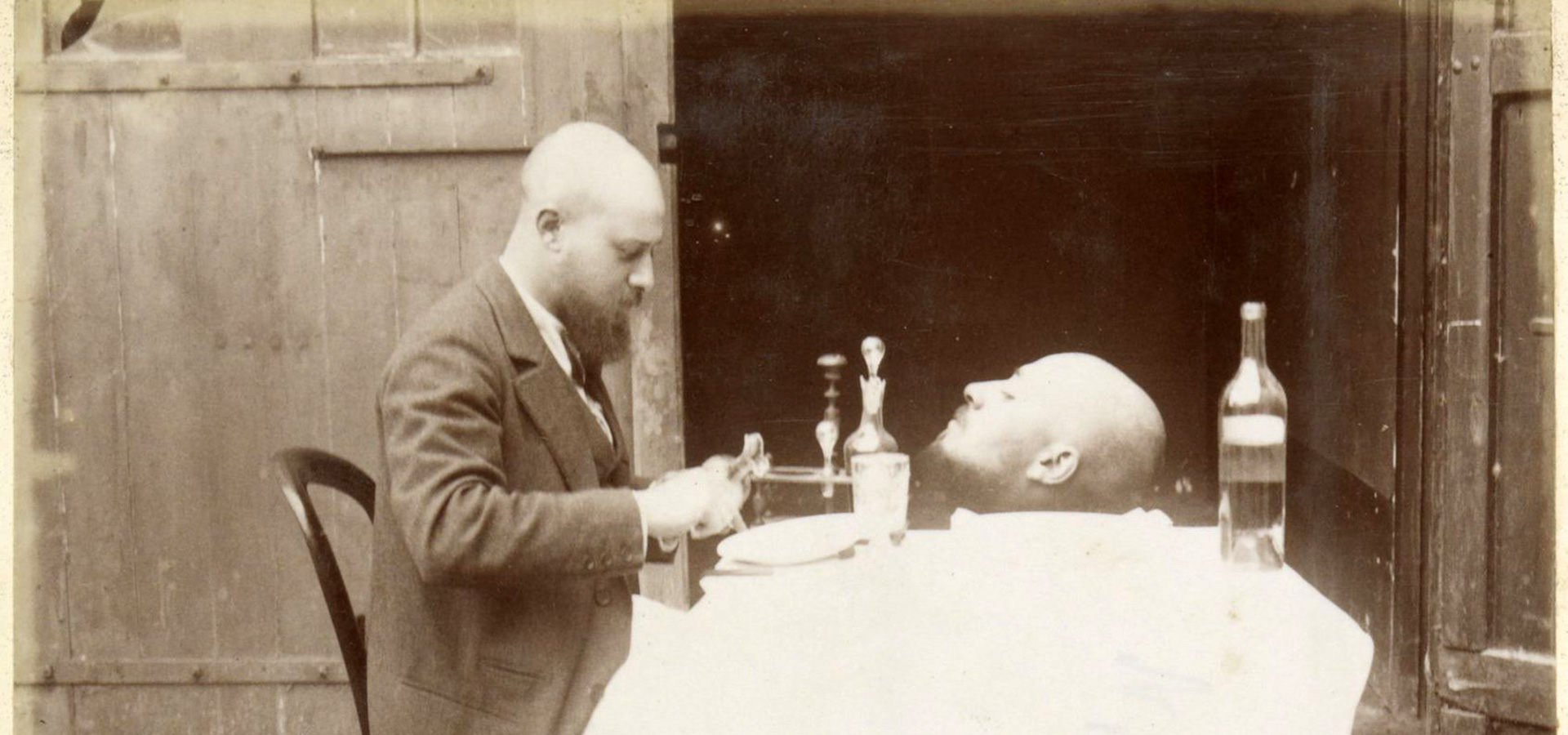

The findings suggest that men experience conflict between their personal preferences and what they think might be expected of them. When they have time to evaluate their decisions, men tend to override their personal preferences and conform to presumed gender expectations. In contrast, women seem to be less concerned with making gender-congruent choices. Irrespective of gender, the issues of eating are tricky: do we eat what we want to eat? Do we eat what we believe we should be eating? Is there a discrepancy between what we eat inside our homes and what we allow ourselves to be seen eating? The simple process of eating is socially constructed to the extent that we eat and drink what is expected of us—and judge others by what we see them eating and drinking. Maybe, being pressed for time, some of us succumb to populist temptations from time to time.

And so the significance of whether or not real men don’t eat quiche can takes us down an existential rabbit-hole. Perhaps it tells us more about those who wish to make such sneering assertions rather than the subjects of their contempt. Maybe the argument now needs to be reverse-engineered and reclaimed by liberal quiche-eaters. Maybe, instead of arguing about what real men might eat, it would help to assert that quiche-eaters don’t vote Brexit; quiche-eaters don’t vote Trump.